Saturday, May 26, 2007

Wednesday, April 25, 2007

“Residents of

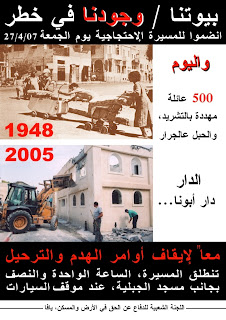

“1948. 2005. and today.”

For over a year and a half,

My dad came to

Over the past few weeks, approximately 500 hundred eviction and demolition orders have been issued by the Israel Land administration and the Amidar housing company to families in Jaffa- mainly in the A’jame and Jabaliya neighborhoods, which are traditionally Arab and prime, beach-front property. These homes are technically illegal buildings, meaning they were built without permits, yet most have been standing for decades.

Several weeks ago I attended an early morning protest at the first home to be slated for demolition. It was an unattractive structure built of concrete and tin, standing amongst several more elegant homes and multiple construction sites, where luxury apartments overlooking the

Most of the 500 families in danger of losing their homes share at least two common traits; they are poor and they are Arab. Additionally, most can probably trace their family ties to the city of

On Friday, a large-scale demonstration took place to protest these eviction and demolition orders. Hundreds of Jaffo natives were joined by hundreds of others, including those of us who have chosen

While these eviction orders are new, the struggle is perennial. For decades, plots of the seaside neighborhoods have been eaten up by developers who build fancy apartments the former residents probably could not afford. And the poster for the demonstration makes reference to 1948, when the Arab population of the city plummeted from 70,000 to less than 5,000.

Since gentrification may be inevitable, I can only hope that

Sunday, February 25, 2007

the work visa revisited

As I’ve mentioned before, I went through a rather lengthy process of procuring a work visa in order to make my life easier. Not only did it give me legal permission to work in this country, it also provided me with a multiple-entry visa valid for an entire year. No more day trips to Jordan to renew visas, no more hassles at border crossings about bending the rules conveniently exiting and re-entering the country every three months, and best of all, no chance of being detained in Denmark again.

But what I forgot to take into account about the work visa was that in placing those 2 full-page stickers into my passport, I became a foreign worker (“you’re Philippino?” one friend asked). The difference between work visa and foreign worker is simple semantics. But being a foreign worker in this country carries weighty implications.

According to Kav La’Oved there are approximately 200,000 foreign workers in

Daily, my life has not changed. In fact, I still haven’t received a paycheck in shekels, so I haven’t actually put the work visa to use. Entering the country, however, is a different story.

Upon my return from

At 5am, the airport was quiet and I stood alone in the corner until someone came out and without explanation returned my passport and allowed me to go on to baggage claim. No one would answer my questions.

When I returned from 10 days in the states this past Friday afternoon,

As an American I could be automatically entitled to the 3-month tourist visa, as a Jew I could become an Israeli citizen, and as a Hebrew speaker I am rarely seen as an outsider or a threat. My B-1 visa overrides all that, and gives me new perspective on what it’s like, although marginally, to be among the unwanted.

Sunday, February 04, 2007

In reality,

Basic facts, both Mikhael of Shovrim Shtika (“Breaking the Silence” –Israeli soldiers talk about the occupied territories) and David, spokesman for the Jewish community of Hevron agreed on. Ten years ago, following the

David laments that the Jews, in reality, have access to only 3% of the city, while Mikhael points out the fact that at the time of this 80/20 partition, there were over 100,000 Palestinian residents of the city and approximately 600 Jews. Additionally, included within the Israeli-controlled 20% are notable landmarks such as the remains of the old city of Hebron, the central market of the modern city and Ma’arat HaMachpelah (Cave of the Patriarchs), where Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Sarah, Rebecca and Leah are believed to be entombed.

When the city was partitioned in 1997 most estimate that 30,000 Palestinians (out of the total 120,000 in the city) were put under Israeli-control in the H2 sector of the city. Since then, life has become increasingly difficult and most who could afford to do so, left, mainly across the blockades into H1. Mikhael quotes a B'Tselem report that 43% have left, while David implies the number is higher and that only 3000-5000 remain.

The central souk (market), 1000 shops which once served the entire undivided city, has been closed by military order because of violence and tension between the Jewish and Palestinian communities. Several main roads in H2 are closed to Palestinian foot and vehicle traffic, even to those whose front doors open to the street, forcing residents to exit via rooftops or become virtual prisoners in their own homes. During the second Intifada, curfew was regularly imposed on Palestinians in the city, forbidding them to leave them homes. Mikhael reports this was the status quo for over 500 days in 2002 and 2003 alone.

The ratio of soldiers to Jewish settlers is 1:1, with additional police and border patrol stationed throughout the city. Both guides mention that today is the best situation

No one disputes that 1929 was an, if not the, integral year in modern Hebronite history, when the mufti of Jerusalem incited Arab residents of the city to riot which resulted in the deaths of 67Jews and the end, more or less, of Jewish settlement in the city until after Israel occupied the West Bank in 1967.

Today’s Jewish community cites this earlier community (that existed pre-establishment of the state of

Mikhael cites a second definitive year in Hebron’s recent history, which David avoids discussing until directly questioned about: 1994, when Jewish resident Baruch Goldstein entered the mosque portion of the Cave of the Patriarchs and massacred 29 praying Muslims, wounding another 150.

David brought us into Beit Hadassah, a former hospital and the first building to be re-settled by the Jewish community in 1979, against the wishes of not only Palestinian Hebronites, but also, the Israeli government. Today this building houses a museum of Jewish history in

Mikhael took us in the home of Hisham and his family, Palestinians who have remained in their house in H2. Hisham spoke to us of the difficulties his family faces navigating forbidden roads. He showed us several videos; of local Jewish children taunting and throwing rocks at Palestinian children on their way home from school and of local Jewish adults breaking into Palestinian homes to heckle during curfew days. He attests that these are regular occurrences.

Ignorance, Mikhael believes, is the largest problem. The vast majority of the Israeli public doesn’t know the details of what goes on in

Tuesday, January 16, 2007

Kivu-Morocco trip makes it on to the Haaretz English website

A search for Jewish roots and Arab neighbors in Morocco

Tuesday, January 02, 2007

on sunday, rabat smelled like barbeque. i imagine the rest of the morocco did as well. i went up to the roof of my friend's apartment building to watch her neighbor, mbarak, and his family slaughter their sheep. from the rooftop, i counted over a dozen other sheep on neighboring buildings meeting, or waiting to meet, the same fate. the sidewalks throughout the city were adorned with drops and pools of blood. as soon as the lamb stopped kicking, mbarak's wife passed out cookies. festivities were underway.

another friend, who is in the peace corps, told me they arent allowed to travel during the week of 'eid al-kabir (the big feast, also known as 'eid al-adha, the feast of sacrifice). leading up to the big day i expected the roast, but couldnt quite see how commemorating abraham's near-sacrifice of his son ishmael could be cause for such a ban.

now i think i understand. 2 days before the 'eid, i tried to make my way back from spain to rabat. after a bus, ferry and taxi, my friend and i arrived at the tangier train station and found it mobbed like nothing we had ever seen. the hordes of moroccans anxious to sacrifice sheep with their loved ones were rushing the doors and picking up metal barricades. we decided we weren't ready to fight that hard for train tickets and we would hired a shared taxi, with our new friends moulay, a moroccan who lives in holland, and his dutch girlfriend, hannuka.

about 1.5 hours into our 3.5 hour trip, the engine made a funny noise and the cab started filling with smoke. we pulled over. although we were about 10 km from a town, the driver insisted that we could only trust his friend who would come from tangier to pick us up. despite our protests, he had the final say. and luckily we managed to crawl the car to a rest stop where we drank tea while we waited out the 2 hours. we eventually made it back to rabat where we even had a home-cooked meal waiting.

yesterday, i tried to beat the post-'eid rush and get down to ouarzazate while the rest of the country sat and digested. my 5 hour train ride to marrakech went pretty smoothly. but then i went against my friends advice and opted for a bus over a shared taxi (since i couldnt bare the thought of 7 people smushed into a mercedes for 5 hours). the bus, like most in morocco, looked to be from my grandparents generation and smelled of exhaust fumes.

although ive taken many moroccan buses before, the road from marrakech to ouarzazate makes me nervous as it contains some of the most windy and dangerous passes through the high atlas mts. the sun set, we reached the snowcaps and other than the fat moroccan in the seat next to me falling on sleep on me, things were ok. 3 hours in, the engine made a bad sound and smoke started pouring out of the bus' underbelly.

broken down for the 2nd time in 4 days, and this time in lesser-traveled snowy mountains, i was less than amused. and this time, i did not have a moroccan, or darija-proficient (moroccan arabic) american friend as a travel companion/translator. i didnt even have european with a name that still makes me crack a smile. we lit fires and waited.

eventually some vans showed up and some of us payed for new rides. i was almost ready to swear off ground transportation and look into splurging on a flight to casablanca. but i think i am going to brave it again with an overnight bus back to rabat tomorrow night.

Wednesday, December 06, 2006

I promised myself I would write again before I went back to misrad hapnim

but I went yesterday. and in the middle of finishing all the paperwork to become a temporary resident, I asked the woman behind the desk why they don’t give work visas anymore.

“what do you mean we don’t give work visas?”

“well, I came in a month ago looking for a work visa, which I was told wasn’t an option. I could chose between aliyah and residency.”

“hang on one second.”

(she goes into the back room for several minutes.)

“no, not really.”

“well why didn’t you tell me??”

and 145 shekels later, I received a multiple-entry work visa good until December 2007.

my 14 or so months in

and since I don’t yet have a job that wants to pay me legally in shekels (my morocco gig offers under-the-table dollars), there was still no real substantive reason for me to do all this hoop jumping. but I haven’t given up hope.

i’m thinking with all the millions of dollars going into the benny sela (escaped serial rapist and